Regional Kabuki and Rural Stages

Even in the very rural north Kanto Plain, in the villages in present-day Hitachi Omiya City, ruled at the time by the Mito clan, it is known from records kept by the head official of Kami-Ohga Village, Kawano Ruheiji, that plays were being performed in local villages in 1751. In 1769, local children enacted a kabuki dance as a sideshow in the festival at Inyosan Shrine in Yamagata, now part of Hitachi Omiya City. Sparked off by the inability to pay the high price demanded for the rental of the children’s costumes, an incident occurred that developed into a movement to have the (rather unpopular) local head official removed from office. Already by this time, kabuki had penetrated so deeply into the lives of the ordinary people that there even existed businesses for renting out costumes to the farmers.

In line with this popularity of kabuki among the common folk, as well as in the towns and cities, stages for performances of ningyo joruri and kabuki began to be built in farming and fishing villages. This trend continued until the late 1920s, and in surveys carried out in the late 60s and early 70s, the existence of over 2,000 rural stages was confirmed throughout Japan. Most of these, however, were permanent stages; very few assembled stages were found.

After the study of the Nishi-Shioko Revolving Stage, a survey found that there are seven stages still in existence in Hitachi Omiya City, including the one at Nishi-Shioko. Although detailed inspections are yet to be carried out, all of these stages are of the assembled type.

At present, the only rural stages that have been found in Ibaraki Prefecture are in Hitachi Omiya City, where several are concentrated in a relatively small area. Assembled stages are also found in the eastern part of Tochigi Prefecture, the upstream area of the Naka River, which flows through Hitachi Omiya City. It is thought that this cultural influence may have been the reason for the construction of the assembled rural stages in the Hitachi Omiya area, but at present this is not well understood.

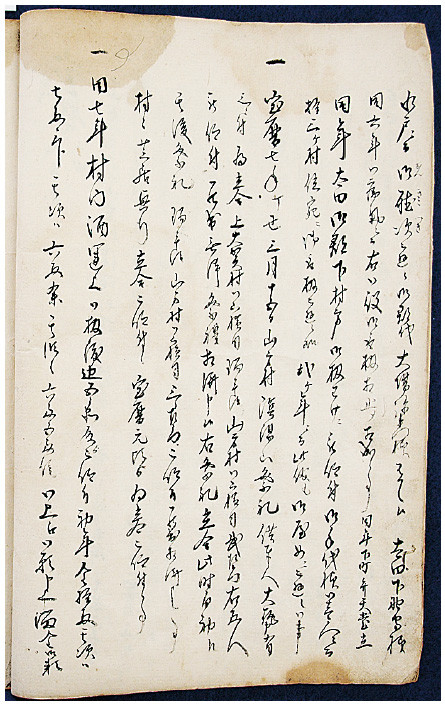

A page from the daily records of the head official of Kami-Ohga Village. In the ninth line (from the right), the record states “Orders came from the Mito clan for the the village heads to be present at performances in the villages of plays by professional actors. This was begun in 1751.”

Judgement on the incident sparked off by the Inyosan Shrine dance costumes, addressed to the father, Yaju, of the boy Unosuke. “At the time of the festival at Yamagata Village Inyosan on March 15 this year, Tajihei took it upon himself to include your son Unosuke in the Kami-Ohga Village group to devote [perform] a [kabuki] dance to the god of the shrine. Since your household is very poor, you refused, saying that it was economically impossible for your son to be included in the dance group. However, you believed Tajihei when he told you that it would not cost anything and you allowed your son to take part in the dance. It turned out that Tajihei had lied and that there would, after all, be a rental fee for the rented costume that was worn during the dance. Therefore, this disorder stems from the problem of who is to pay the rental fee.”

常陸大宮市ふるさと文化で人と地域を元気にする事業

常陸大宮市ふるさと文化で人と地域を元気にする事業