Performances of Village Plays as Seen from Old Documents

Around 40 documents concerning the Nishi-Shioko Revolving Stage have been preserved to the present day. These cover roughly a century from 1823 to 1933 and mainly describe plays performed as part of the ceremonies accompanying the rebuilding of the Chinshu Shrine and Haguro-Kashima Shrine in Nishi-Shioko. A careful reading of these documents reveals how much the plays cost to put on and how the funds were procured.

The largest shrine festivals in the village were carried out to accompany the occasional rebuilding and repair of shrines. The plays performed at that time were known as Ohshibaya (oh is “big” and shibaya is the local dialect for “a play”, shibai being the standard Japanese word for “a play”) and were always carried out over two evenings. It is reported that at shrine festivals such as the arashiyoke, a ceremony held to ward off typhoons before the rice-harvesting season, in which the young people of the village played the leading role, plays were performed for only one night, professional actors being asked to come to the village from nearby Iino (now Motegi Town in Tochigi Prefecture). For the Ohshibaya, however, actors demanding high fees were invited to the village to perform. At the last shrine-rebuilding festival to be held, in 1933, the Tokyo kabuki theatre company Matsuba-za is said to have performed in the village.

Looking at the most well-preserved documents, those of the shrine-rebuilding festival plays of 1902, the total costs were just over 600 yen in the money of the time. In terms of the value of the yen today, this would represent around eight million yen (US$80,000 at 100 yen per US$). It is very surprising that a village of about 70 households could hold a festival costing this much money in an era when cash incomes were very low.

Let’s take a look at the breakdown of the income for the plays. Conspicuous among the items are the “miscellaneous auction income,” money gained from auctioning off timber and bamboo following the dismantling of the stage and the waste paper remaining from the lanterns, and the “young people’s income,” gained as fees for the rental of the stage to other villages (and which was the fund that drove the village financial system). Special mention should also be made of the tarudai and ikki-tarudai, which together account for 40% of the income. These are the festive donations, known as hana, given by people who have come to see the plays, and show how the key to putting on a successful play performance was in the numbers of people that could be attracted to the village as the audience.

While the tarudai were festive donations given to the Nishi-Shioko area, the ikki-tarudai was money given to individuals living in Nishi-Shioko. Interestingly, after settling all the accounts for the shrine festival, any shortfall was paid out of the ikki-tarudai, which was then handed over to the individuals after a deduction of a certain percentage from each donation. When the tarudai were written into the receipt book, the addresses of the donors were also recorded, and thus it is possible to know where the spectators came from.

Expenditures by the local people for this major village festival were a great burden, but the items that could be provided locally, such as materials for the stage and oil for the lanterns, were bought from villagers, and accommodation expenses were paid to villagers who put up the actors while they were in the village, and thus there were opportunities for making cash income separately from the festival donations. In a short period of time, there would have been repeated expenditures and incomes, causing cash to circulate in the community at a much faster rate than normal. Items that could not be bought in the local area had to be purchased from a shop in the town, this money amounting to a surprisingly large 177 yen. Large amounts of sake were bought from local sake breweries and it is easy to see how the village festivals acted as a catalyst stimulating the wider area, including the towns.

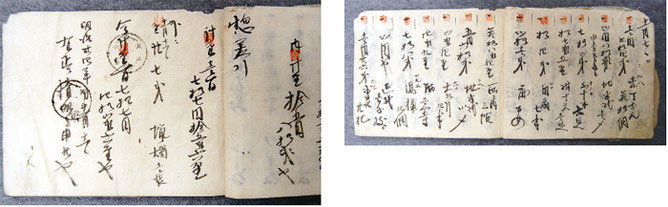

“Purchasing Records”. A notebook recording goods purchased at the Iseya shop in Omiya. In addition to the reed and straw mats for covering the roof and for the audience to sit on, raw foods for cooking boiled food, candles, paper lanterns, paper, Japanese tabi socks, and so on are recorded. The total payment was 177 yen (around two million yen in present-day terms). (1902)

Notebook recording various items, such as timber and reed mats, used for the plays and later auctioned off to help defray the costs of the performances. Buying items at auction was probably cheaper than buying new items. Waste paper was also considered as a resource. (1893)

A list of names of the people who played a role in the shrine-rebuilding plays. The hanageshi (a gift given in return for a hana donation) was cooked red rice and sake. It appears that the amount given was fixed in proportion to the donation received and the people in charge of this were the “sake and red rice measuring clerks”. Cooking was carried out by the “red rice cooking and dyeing staff”. The “stagehands” were the central people responsible for the assembly of the stage and its operations, including the rotation of the stage when necessary. (1902)

常陸大宮市ふるさと文化で人と地域を元気にする事業

常陸大宮市ふるさと文化で人と地域を元気にする事業